Consciously or unconsciously, positively or adversely, our parents influence our lifestyle decisions and career choices. And we don’t choose our parents, although those who believe in the journey of the soul say we do.

Regardless of what we believe, having a good father is a gift to treasure. Supportive, loving fathers give their children self-esteem, courage and purpose.

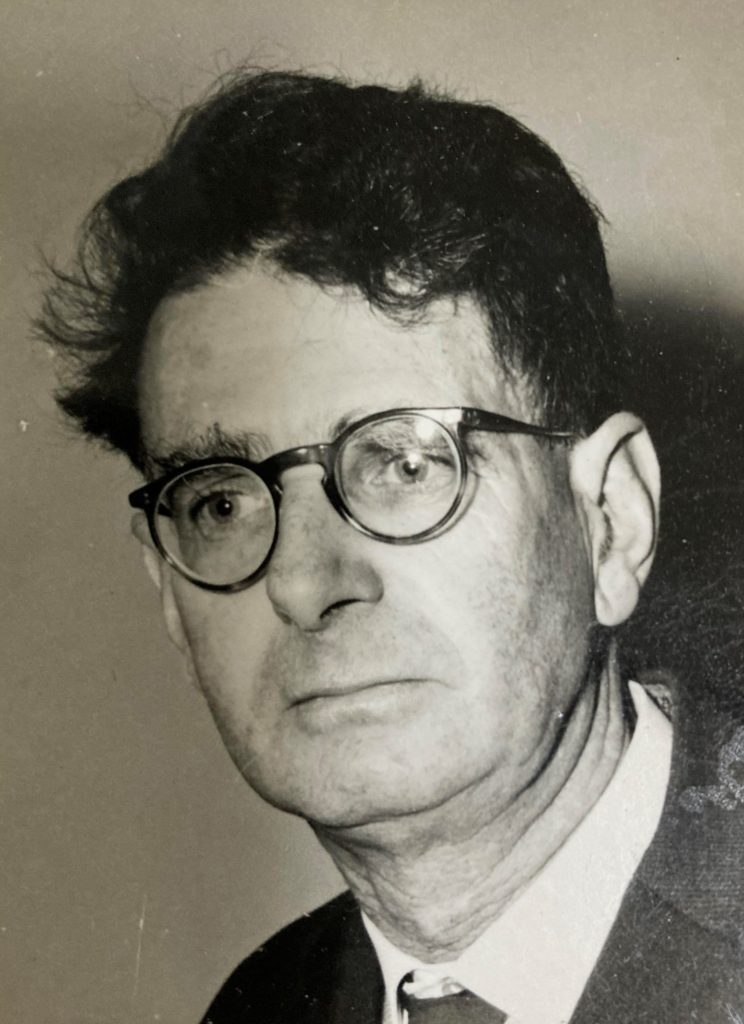

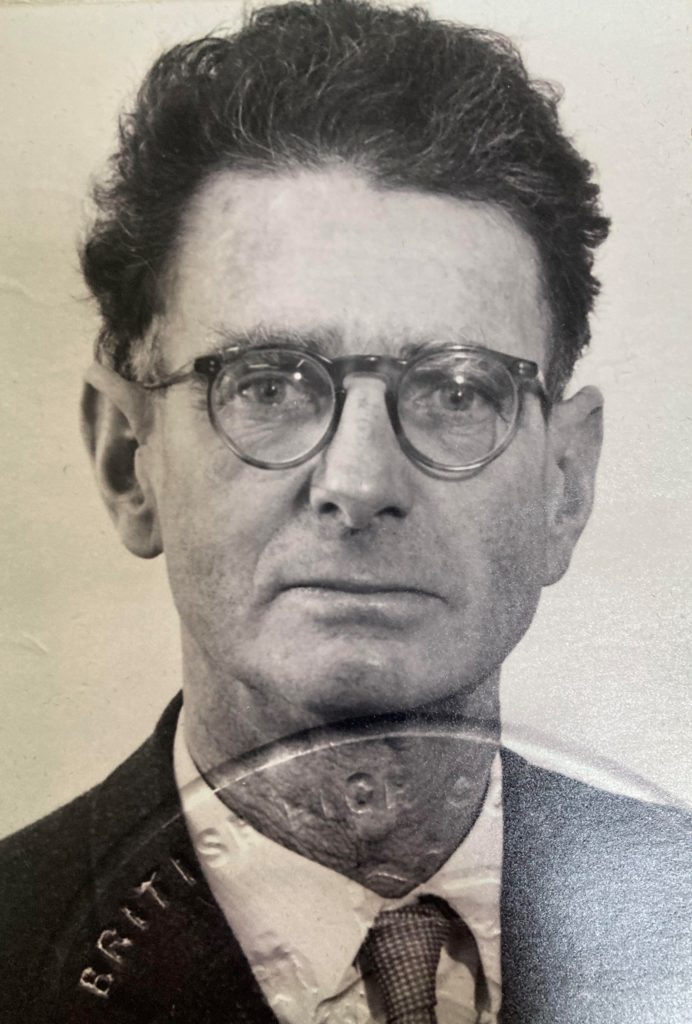

My father, John Banwell, a geophysicist who would be 113 today, encouraged my whimsical career choice, teaching me to appreciate the wonders of science as well as the power of magical thinking. We need creators, dreamers and visionaries as well as dissectors, realists, and rationalists in today’s world. Both veins of thought shape human civilization and the timeless words of Desiderata still ring so true: ‘Keep interested in your career, however humble; it is a real possession in the changing fortunes of time.’

Although this beautiful, modest man would have run a mile from attention-seeking social media sites, I want to pay tribute to his wisdom, kindness and humility today on his birthday. Born in 1908, he died too soon, when I was 25.

My mother once called my father John Banwell a fathomless man of many talents. A geophysicist, piano player, eclectic reader and some-time kiwi fruit horticulturalist, he was as good at fixing locks, pruning trees and building stylish hutches for my numerous pet birds, rabbits and guinea pigs, as he was at pondering and unravelling the mysteries of the universe. He introduced me to science fiction when I was 12 and directed me to possible descriptions of alien visitations recorded in the Bible (Ezekiel 1- 4). He taught my brother and me to revere nature’s wondrous creations, including the terrifying-looking but completely harmless New Zealand weta, which we frequently came across in our wood piles.

Unruly Toddlers and Time Travel

I grew up in New Zealand surrounded by natural beauty, books, art, trees, exciting ideas and lively family conversations. I loved the measured way Dad read me bedtime stories. He had a beautiful voice – soothing and deep.

Sometimes his solutions to challenges – particularly regarding the matter of child care – were unusual. Such as the time when he tied my toddler brother to the rotary washing line so he could mow the lawn without interruption. My mother, when she came home from the shops, was furious. When she recounted that story, she introduced me to the German word: Fachidiot. That’s a highly specialized and qualified someone who trips over his own feet, spills wine over the hostess at social gatherings and forgets to put out the rubbish. Fachidiots are the kind of people who tie toddlers (Dad defended himself by explaining he did give Martin a few feet of rope so he could roam …) to washing lines.

Despite his approach to childcare which today might land him in a heap of trouble, Dad never shied away from my frequent impossible-to answer questions, those childhood ‘whys?’ When I asked him once if it would be possible to time travel, he simply said that perhaps one day, but it would take an extraordinary amount of energy.

Energy, of course, was his specialty. An advocate of clean, green energy way before it was a big thing, his work as a geophysicist took the family from Taupo – the steamy geothermal heart of New Zealand – to Mexico City and New York.

Fiery Fumaroles

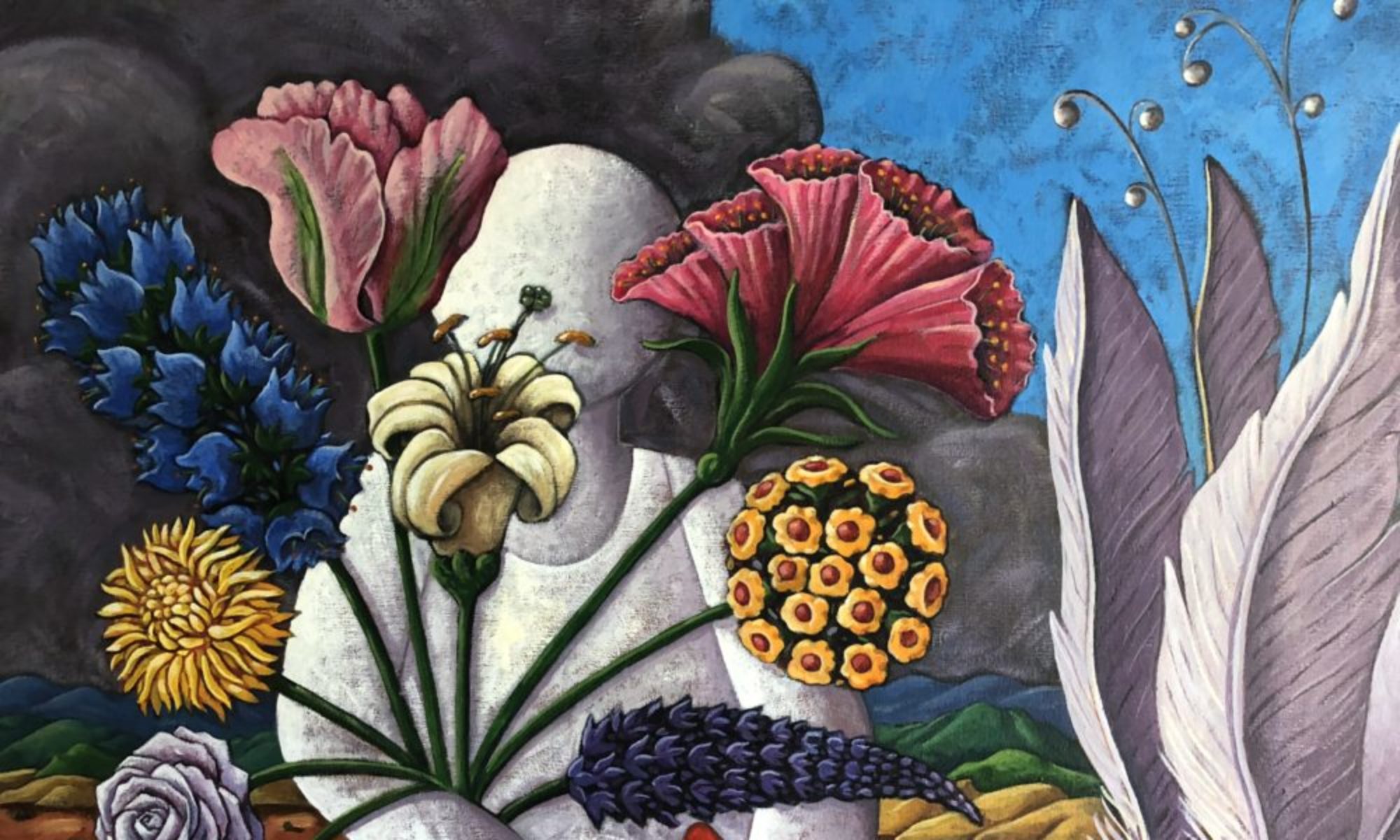

In Mexico, he once accompanied a group of fellow geophysicists to Los Humeros, a volcanically active area where they named the fumaroles after their daughters. So, somewhere in Mexico, there’s a fumarole (a hole in the earth emitting hot sulphurous gases) named Ingrid. Aside from the troublesome affiliation between females and fumaroles (I suspect this was Latino machismo at play), he always made me feel special. And he revered and adored my mother. She was as fiery as he was calm. As social as he was quiet.

My brother and I grew up in a loving family where our parents were different, but equal. When Dad’s work for the United Nations took us to New York City, I attended the United Nations International School – a place of myriad nationalities – all different but equal. What a wonderful school. What an astonishing, enriching experience. This was all thanks to a restless father never content with the nine-to-five business. He wanted to change the world through science. Make it a better, more peaceful and enlightened place. Science was not his job, but his calling.

The Full Works

Calm and rational, he wasn’t one for outbursts, yet I’ll never forget the time he discovered I’d been smoking in my bedroom. Bristling over breakfast, the following morning he told me firmly, in a controlled geyser of fury, that he would not tolerate such a disgusting, unhealthy habit. His words stayed with me and I have never been a smoker.

Another day when I was fifteen and weeping over some boy, he told me I must always be independent. That’s another piece of wisdom that has stayed with me. His head ruled his heart and he taught me to do the same; to think before acting, consider different perspectives and independently investigate the truth.

He was a quiet man, but when he blew his nose, sparrows fled from the surrounding trees. At night, his snores shook the windows. He even looked like a scientist, with a magnificent head of unruly black, wavy curls that refused to obey the laws of physics. Until he needed a passport photo. Then, the scissors – attached to my mother – came out.

When he left his job at the UN and we returned to New Zealand, he brought with him one of the very first computers – an extortionately expensive Hewlett Packard slightly larger than a typewriter. With a small blue screen, the size of a scotch finger, it grunted, beeped, squeaked and, when he fed it cash register rolls, spat out reams of squiggles that sent him into scientific raptures. My mother was one of the world’s first computer widows, neglected by a husband who spent hours in his office seduced by the siren call of that beguiling contraption.

With his frequently distracted, absent-minded air, he wasn’t someone prone to glib commentary or superficial social chit chat. If you asked him a question, you got the full, considered works in his reply.

He was also an enthusiastic demonstrator of nature’s powers, once introducing my brother and me to static electricity by sitting near a heater and vigorously stroking our cat’s fur before earthing him on the carpet. Despite the crackles, sparks and hisses, the cat always came back for more – those electric shocks a small price to pay for the warm lap and enthusiastic strokes of that gentle geophysicist.

A Real Man

John Banwell’s mind never stopped inquiring. In the days before he passed away from a sudden coronary thrombosis, he was conducting solar energy experiments in the family garden, using tin cans, wires, and a collection of other mysterious cobbled-together instruments, neatly recording the results in a notebook.

I remember always feeling encouraged. Respected. Loved. Never judged. He never, never, made me feel less for being female. I thought this was the way the world worked. But back in the nineteen seventies and eighties, as a young woman, I stepped into a very different landscape. After taking his paternal nourishment for granted, I entered a world where women were often looked down on, bullied, disrespected, exploited, oppressed, stalked, taunted and harassed. It was a rude shock.

Over forty years later, it seems astonishing that so little has changed. Navigating this world is still a challenge for many women.

So, I want to also pay tribute here to the fathers in the world who encourage their daughters to be self-respecting and independent, the men who set fine examples of manhood to their sons. Being a real man means being brave enough to be gentle and loving, open-minded, empathetic, respectful and encouraging. Being a real man means being a man like my father, John Banwell.

Thank you, Dad, for all your love and all your gifts. Happy 113th Birthday.

Thank you for those precious 25 years. I couldn’t have wished for, or dreamed of, a more perfect father. Your love, warmth and encouragement remain an inner fortress lit by a never-ending glow. You were and always will be, a treasure.