Although we lived in Mexico City during the 1968 Olympics, I don’t remember giving a damn. We weren’t a sporty family. My world was built from books and drawings, animals and dreams.

Max – our golden hamster – was the family athlete. During the day that crepuscular rodent slept, but in the evenings, he transformed into a creature as frenetic as an Olympian on steroids. He lived in an enormous clay bowl under the stairs, spending his nights crawling in and out of empty toilet rolls, running on his hamster wheel, and trying to escape.

Sometimes, he succeeded. Once, we found him under the fridge, eventually enticing him out with lettuce leaves. Another time he vanished for several days. Early one morning, we heard the hamster wheel squeaking and found him back inside his bowl, running a marathon.

We didn’t know back then that Max was training for the Big Event.

One night while we were all asleep, he stacked the toilet rolls on top of one another, stocked his cheek-pouches with food, long-jumped from his bowl and vanished.

My parents assured me he would eventually turn up. He didn’t.

For several days, we left pieces of watermelon, tortilla and avocado around the house – altarpieces for our itinerant god. The food lay untouched. A hamster-sized piece of my eleven-year-old heart missing, I wept and lost my appetite.

Max’s wheel quietly sat inside his bowl like a ride at an abandoned Lilliputian amusement park.

Meanwhile, the world still turned. Olympian triumphs and scandals filled the news. Our home country of New Zealand won a gold medal in rowing, two black American sprinters raised their fists in a human rights salute during the medal ceremony. I listened dully from my haze of sorrow. How could people protest and celebrate when my hamster was missing?

At night, I lay awake yearning for the squeaks and soft rustlings of my peripatetic Olympian. All I heard was carnival music wafting from the valley of slums beyond our suburb’s terraced and bougainvillea-flossed gardens.

Day after day, I languished in my hamster-less void.

My parents tried to distract me. We visited a marketplace where I met a beetle covered in costume jewels, a chain and safety-pin glued to its back. That living arthropod brooch amplified my grief.

Two weeks after Max’s disappearance, signs appeared – shredded pages in my brother’s maths textbook, a watermelon seed, a piece of disgorged carrot on the top floor landing.

A barnyard tang, initially indistinguishable from the scent of a fourteen-year old boy, drifted from my brother’s bedroom. Deciding one Saturday to make his bed, he discovered a ragged circular hole in his sheet.

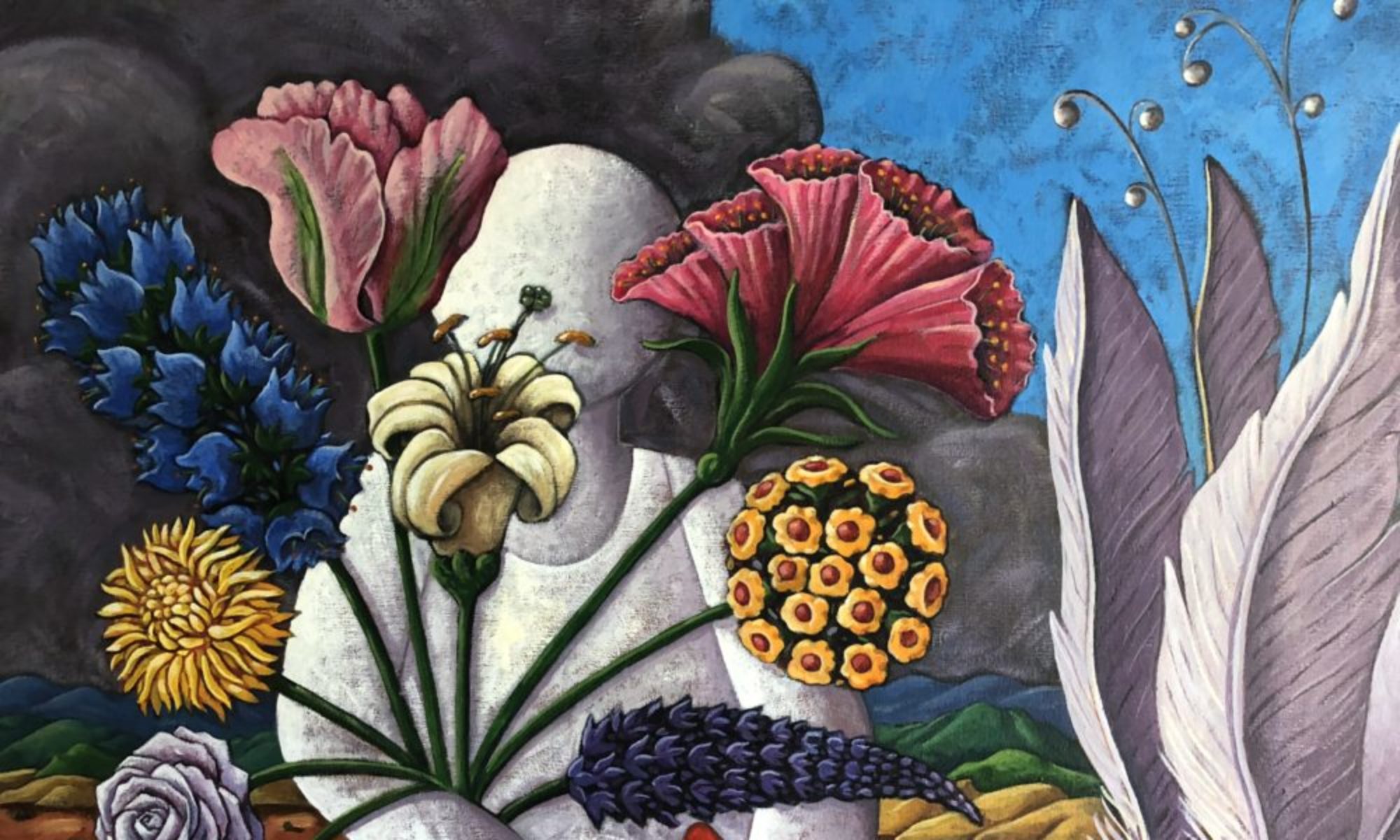

And there in a dark corner under his bed, my brother found a temple built from droppings, seeds, tortilla, shreds of blue-grid maths book and pieces of cotton sheet. Burrowed inside lay a tiny, curled-up, sleeping Buddha.

My heart leapt with grateful joy as he placed that furry gold medal into my waiting hands.

Once more, my world was whole.